Speed Control

This article describes the use of speed control by air traffic controllers to manage the traffic flow and solve conflicts. It is focused on the en-route phase and describes the general provisions, typical uses and also gives some advice about the practical use of the method. Note that the advice is derived mostly from good practices and experience, and is in no way intended to replace or supersede local procedures and instructions.

Description

Speed control is used to facilitate a safe and orderly flow of traffic. This is achieved by instructions to adjust speed in a specified manner.

Speed adjustments should be limited to those necessary to establish and/or maintain a desired separation minimum or spacing. Instructions involving frequent changes of speed, including alternate speed increases and decreases, should be avoided. Aircraft should be advised when a speed control restriction is no longer required. The flight crew should inform ATC if unable to comply with a speed instruction.

The future position of an aircraft (and, consequently, separation) is determined by the ground speed. Since it is impractical to use it directly, the indicated airspeed (IAS) and Mach number are used instead to achieve the desired ground speed. At levels at or above FL 250, speed adjustments should be expressed in multiples of 0.01 Mach. At levels below FL 250, speed adjustments should be expressed in multiples of 10 kt based on IAS. It is the controller's task to calculate the necessary IAS or Mach number that would result in the appropriate ground speed. The following factors need to be taken into account:

- Aircraft type (range of appropriate speeds)

- Wind speed and direction (in case the two aircraft are not on the same flight path)

- Phase of flight (climb, cruise, descent)

- Aircraft level (especially if the two aircraft are at different levels)

Restrictions on the use of speed control:

- Speed control is not to be applied to aircraft in a holding pattern.

- Speed control should not be applied to aircraft after passing 4 NM from the threshold on final approach.

Phraseology

- Report indicated airspeed / report mach number / speed (in case the current speed cannot be obtained by other means, e.g. Mode S information)

- Maintain/increase/reduce [speed] [or greater/or less] [reason] [condition]. Examples:

- Maintain 300 knots or greater

- Maintain Mach .83 or less due converging traffic until [point name]

- Reduce speed 260 knots or less for sequencing

- Increase speed Mach .82 or greater for the next 10 minutes.

- Resume normal speed (cancels a previously imposed speed restriction)

- No *ATC* speed restrictions (cancels a previously imposed speed restriction)

- On conversion [speed]. This instruction is sometimes used for climbing or descending aircraft when the speed control includes the moment of swithcing between IAS and Mach number. Note: while this instruction is used in a number of countries, it is not part of the ICAO standard phraseology.

Typical Uses

- Separation adjustment (e.g. two successive aircraft are separated by 9 NM and the required separation over the FIR exit point is 10 NM)

- Separation preservation (e.g. two successive aircraft have the necessary separation but this may change if one of them or both change their speed)

- Delay absorption (an alternative to flying a holding pattern)

- Avoid or reduce vectoring:

- in some situations speed control may be used instead of vectoring

- in some situations speed control may be used in combination with a vectoring instruction, in order to reduce the time an aircraft flies on heading and/or the heading change.

Rules of Thumb

- Generally, 0.01 M equals 6 kt

- Speed difference of 6 kt gives 1 NM in 10 minutes

- Speed difference of 30 kt gives 1 NM per 2 minutes

- Speed difference of 60 kt gives 1 NM per minute

Benefits

- Speed control is often the most efficient way for solving conflicts and traffic sequencing.

- The added workload is relatively low, especially for thinner sectors where most level changes need to be coordinated with the neighbouring upper/lower sector.

Things to Consider

- Transition times should be taken into account. It usually takes a few minutes before the aircraft reaches the desired speed due to inertia.

- When an aircraft is heavily loaded and at a high level, its ability to change speed may be very limited.

- Aircraft experiencing turbulence often fly at reduced speed. Under such circumstances it is advisable to coordinate instructions for speed increase with the flight crew.

- Speed control needs more time to achieve the necessary separation compared to other methods (vectoring, level change, vertical speed control). For shorther ATS sectors (e.g. 10 minutes transit time) this method is effective for:

- Separation adjustment (e.g. if the aircraft already have some separation and need a few NM more, this could be achieved by speed control even in shorter ATS sectors)

- Preservation of achieved separation (e.g. if two successive aircraft of similar type already have the nevessary separation, an instruction to maintain the same speed would be appropriate)

- Impact of wind. Winds can make a slower aircraft (in terms of M or IAS) have higher groundspeed than a faster one. In a complex situation, it is usually better to use speed control for successive aircraft and other method (e.g. level change) for a converging conflict.

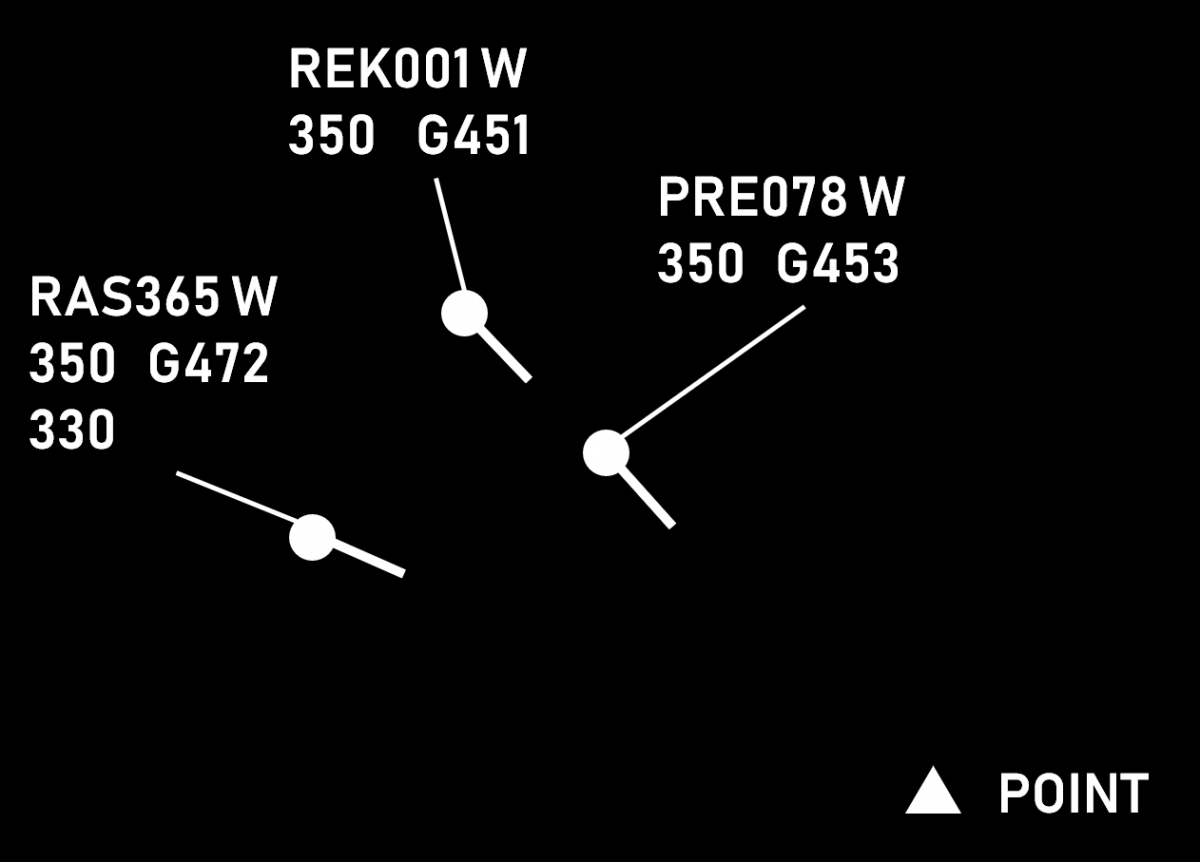

In this situation the three aircraft are of the same type and flying with the same Mach number. However, due to the strong winds, RAS365 is considerably faster. It is therefore advisable to use speed control for PRE078 (e.g. M078 or greater) and REK001 (e.g. M078 or less) and change the level of RAS365 (in this case, descend to FL330). - Maintaining the Mach number during climb (in unchanged wind) results in reduction of TAS (and therefore groundspeed). It is therefore possible that a succeeding aircraft catches up with the preceeding one even if the preceeding aircraft is assigned a higher speed.

- Maintaining IAS during descent (in unchanged wind) results in reduction of TAS (and therefore groundspeed). It is therefore possible that a succeeding aircraft catches up with the preceeding one even if the preceeding aircraft is assigned a higher speed.

- An instruction for speed reduction is generally incompatible with one for maintaining a high rate of descent. Such combinations are best avoided and should only be used after explicit coordination with the flight crew that the desired combination of lateral and vertical speeds is achievable.

- Speed reductions to less than 250 kt IAS for turbojet aircraft should be applied only after coordination with the flight crew.

Source: www.skybrary.aero