Level Change

While there are various reasons for a level change, this article focuses on the conflict solving aspect.

Description

Changing an aircraft's level is often the easiest way for a controller to solve a conflict, i.e. a situation where two (or more) aircraft are expected to be closer than the prescribed separation minima.

Advantages:

- Comparatively smaller intervention. The aircraft continues to fly using own navigation (as opposed to vectoring) and follows the planned route (as opposed to proceeding direct to some distant waypoint).

- Faster to achieve. Even when the aircraft is to climb or descend by 2000 ft, only 1000 are often enough to ensure separation with the conflicting aircraft (see section Opposite Levels for details). This means that the conflict is usually solved within less than a minute.

- Easier to monitor on a situation display. Wind can influence both aircraft speed and flight direction. Additionally, speed vectors can change direction due to specifics of the surveillance system (especially the presence or absence of a tracker). On the other hand, all modern ATS systems provide an indication for climb or descend (an arrow next to the aircraft level). This makes it much easier for a controller to monitor aircraft compliance.

- Less controller workload. Changing an aircraft's level normally requires one instruction and about a minute to achieve the required separation. By contrast, speed control usually requires prolonged monitoring (the required separation "builds up" gradually). Vectoring requires more instructions - at least one for the heading change and one for the return to own navigation but more can be necessary depending on the circumstances. This will also require a longer period of monitoring.

Disadvantages:

- The main disadvantage of a level change is that aircraft normally fly at their optimal cruise levels. Therefore, any level change leads to reduced efficiency. This effect gets worse when increasing the difference between the desired and the cleared level.

- The use of temporary level change (i.e. the aircraft climbs/descends to a safe level to solve a crossing conflict and then returns to its cruising level) requires two vertical movements (one climb and one descend) which is also sub-optimal in terms of efficiency.

- There is an inherent risk of a blind spot, i.e. the controller may solve a medium term (e.g. 15 minutes ahead) conflict while at the same time create a new one with an aircraft just below or above the one being instructed to change level.

- When vertically split sectors are used, the level change may require coordination with an adjacent upper or lower sector which increases the workload for both controllers.

Climb Vs. Descent

After deciding to solve a conflict by a level change, the controller must choose between climb and descent. The former is generally preferred, as it leads to better flight efficiency. However, in some situations descent is the better (or the only) option, e.g.:

- The aircraft is unable to climb due to weight. Note that weight reduces as fuel is burnt so a higher level may be acceptable later. In this case the controller should take into account that the climb rate could be less than usual.

- The aircraft is approaching its top-of-descent. Instructing an aircraft to climb shortly before it would request descent is not very beneficial to flight efficiency and can increase controller workload (the higher the aircraft, the more potential for conflicts during the descent).

- Turbulence is reported at the higher level. Vectoring, direct route or speed control are generally preferable in this situation.

- The manoeuvre is to be performed quickly (e.g. due to a conflict being detected late). In this case, if a climb instruction is issued, it may be declined by the crew, thus losing precious time.

If the controller is in doubt as of which option is preferable (and if both are available), the controller may first ask the pilot (time and workload permitting). The fact that the range of available speeds is reduced at higher levels should also be considered. If the climb is to be combined with a speed restriction, this should be coordinated with the crew beforehand.

Opposite Levels

In many situations a level change would require the aircraft to climb or descend by 2000 feet (so that the new level is appropriate to the direction of the flight). However, sometimes it is better to use an opposite level, i.e. one that is only 1000 feet above/below. This is often a good solution in case of crossing conflicts, i.e. where the paths of the two aircraft only intersect at one point and the level change is expected to be temporary.

- The solution is better in terms of flight efficiency because the aircraft will fly as close as possible to the desired level and the need for vertical movement will be reduced

- The opposite level may happen to be within the own sector, therefore no coordination with an adjacent upper or lower sector would be necessary. This reduces the workload of both controllers and is especially useful when there are multiple, vertically-split sectors.

It should be noted, that a few risks exist with this solution:

- If there is a flight on an opposite track, the normally expected 1000 ft separation would not exist

- In case of radio communication failure, the aircraft may fly at an opposite level much longer than expected and the exact moment of returning to the previous level may not be easy to determine.

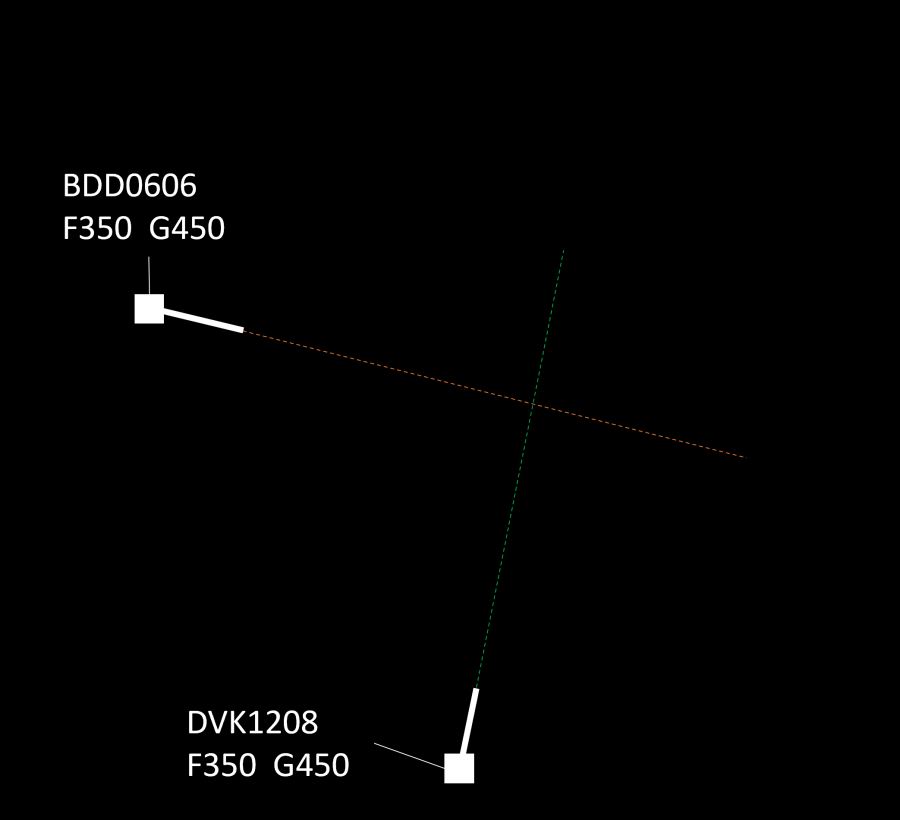

The picture below show a situation where the use of opposite level is preferable. The level change will be required for a few minutes only and there is no opposite traffic.

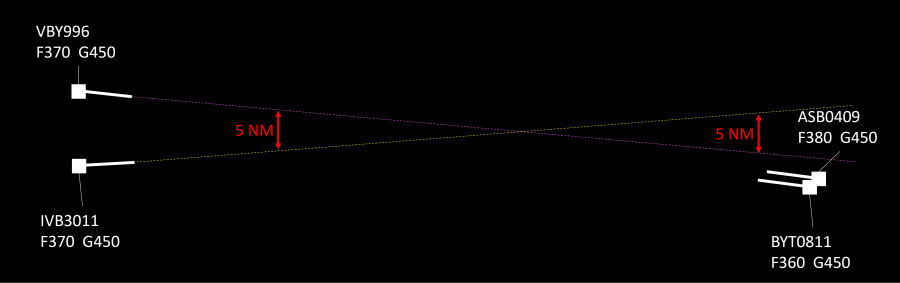

The picture below show a situation where the use of opposite level is not feasible because of opposite traffic. Therefore, a level change of 2000 ft is preferable.

The use of opposite levels can sometimes be justified when the conflict is at the sector exit point. This solution, however, is subject to approval from the downstream controller. The feasibility of this option depends on the geometry of the conflict (are the aircraft diverging after the point of conflict) and on the traffic situation (are there aircraft that are flying at the same level on an opposite track).

Priorities

As a general rule, when two aircraft are at the same cruising level, the preceding aircraft would have priority, i.e. the succeeding aircraft will have to climb or descend. Other criteria may be specified in the manual of operations or other documents containing local procedures. In any case, the controller may deviate from these procedures based on the traffic situation. For example, if changing the level of the succeeding aircraft would create a new conflict (and thus, a new intervention would be necessary), the controller may opt to work with the preceding aircraft. Naturally, flights in distress, or those performing SAR operations, would have priority over other traffic. This includes obtaining (or maintaining) the desired level while a lower priority traffic (e.g. a commercial or general aviation flight) would have to change level. Other priorities may be specified in local procedures (e.g. flights with head of state on board).

Vertical Speed Considerations

Normally, vertical speed is not considered an issue in case of a level change solution to a conflict. This is because in most cases the instruction is issued well in advance (5-15 minutes before the potential separation breach) and the level change is 1000 or 2000 ft, which means that vertical separation will be achieved comfortably prior to losing the required horizontal spacing. Nevertheless, there are some situations where it might be necessary to ensure that the vertical speed will be sufficient. These include:

- There is a reason to believe that the aircraft will not (be able to) climb fast, e.g. a heavy long-haul flight in the initial cruise stage, the aircraft type is known to climb slower than others, the new level is near the ceiling, etc. While 1000 ft/min means that 1000 ft separation will be achieved in one minute, if the rate drops to 200 ft/min, the required time will be 5 minutes. In the scenario where 2000 ft level change is necessary (e.g. converging traffic at the sector exit point and an opposite traffic 1000 ft above), a 200-300 ft/min climb rate will result in a 7-10 minute climb.

- Sometimes, if a descent rate is not specified, the manoeuvre may start at rates in the range of 500 ft/min. In this case, a 2000 ft level change will require 4 minutes as opposed to only 1 or 2 if "normal" vertical speeds of 1000-2000 ft/min are used.

In such situations the controller should either:

- ensure the vertical speed will be sufficient (e.g. by specifying a desired rate of climb or descent), or

- issued the instruction early enough, or

- if the above are not possible, an use an alternative solution.

Source: www.skybrary.aero